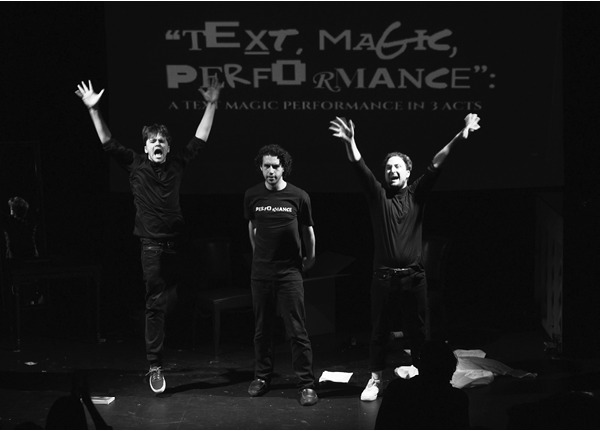

TEXT, MAGIC, PERFORMANCE: A TEXT MAGIC PERFORMANCE IN 3 ACTS

first performed on September 20, 2018

The Tank, New York, NY

performed three times in 2018

NATHANIEL JAMESON / ALEX SALTIEL

Adam Obedian, Simon Broucke

New York, NY

886882589n886882589c886882589j886882589188688258998868825892886882589@886882589g886882589m886882589a886882589i886882589l886882589.886882589c886882589o886882589m

TEXT, MAGIC, PERFORMANCE: A TEXT MAGIC PERFORMANCE IN 3 ACTS

NATHANIEL JAMESON / ALEX SALTIEL

We believe the present moment to be predominantly characterized by an oversaturation of information. As a result, a friction is created between meaning and meaninglessness: the foundations of human experience are diluted to cliché, and surprise becomes almost impossible to facilitate. In order to surmount these feedback loops, we sought to reproduce the chaos of hypermodernity through the context of live performance. “Text, Magic, Performance” was our experiment to see if theater could go beyond discourse in order to touch life.

Combining the aesthetics of powerpoint comedy, “magical” spectacle, and traditional theatrical performance, the show both lampoons and highlights its connections to academic theory as a way of examining the natures of performativity, subjectivity, and reality. As the audience enters the dimly-lit space, the show has already begun: onstage, we sit, wearing neutral white masks. After a lengthy piano introduction performed by a third mysterious individual, we unmask and begin a ninety minute comic fugue that continually devalues and revalues audience expectation. Throughout, powerpoint projections constantly pop up and recontextualize specific lines and quotes in order to further obfuscate intention and satirize our own efforts. To further aid in this “distancing” effect, we always carry our scripts onstage.

The show itself is in three acts: Text, Magic, and Performance. In “Text,” we use excerpts from canonical readings as jumping off points for vaudevillian free association that toes the line between educational and inane. In “Magic,” we reproduce commercial stage magic through a sleight-of-hand card trick as well as a simulated trance, playing upon Freudian tropes of the subconscious mind. Throughout these two acts, we make constant use of audience participation, some of which is obviously staged. Two pronounced examples are a tiny baby doll whom we refer to as “The Gentleman” and our friend, Adam Obedian, whom we constantly call onstage to berate. In “Performance,” we invite Adam onstage one last time to read some closing remarks on the nature of the theater. Subverting all expectation, he performs a meticulously rehearsed, non-ironic, and genuinely beautiful monologue that reanimates the meaning we have persistently undervalued. Thus, in concluding this odyssey of ostensible meaninglessness, we finally touch on something collectively real. To extend this celebratory feeling, we hold a short, post-bow talkback to engage the audience. After which, we return to our seats, put on our masks, and reset the space as if the whole performance was a dream. Maybe it was.