N 49.39’7.92” W 124.4’11.397”

first performed on July 7, 2018

Forest, Shíshálh Nation, Canada

performed seven times in 2018

BETHANY HUGHES

New York, NY

523761383b523761383e523761383t523761383h523761383.523761383l523761383a523761383u523761383r523761383e523761383l523761383l523761383e523761383@523761383g523761383m523761383a523761383i523761383l523761383.523761383c523761383o523761383m

bethanyhughes.ca

N 49.39’7.92” W 124.4’11.397”

BETHANY HUGHES

Everything is not given. Exchange opens a dialogue. This durational performance begins with acknowledging where the work is created, on and between the traditional unceded territories of the Squamish (skwxwú7mesh), Sechelt (shíshálh), Sliammon (tla’Amin), and Kla’hoose First Nations.

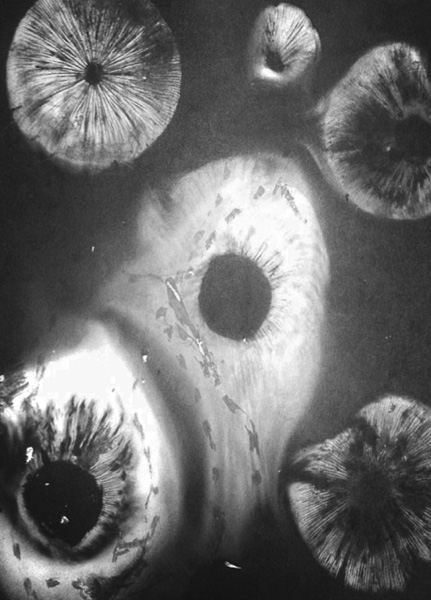

For seven days I walked silently around old growth forests northwest of Vancouver, foraging mushrooms in whatever containers I had on me, pockets, paper bags, or my hands. Each night I returned to a screened-in porch at a friend’s cabin where I was staying. There was a small bed for people passing through and a table for laying out harvests. Before sleeping I would remove each mushroom’s stem, place the gills down on paper and cover with a glass bowl overnight to develop a print. Under this seal mycelium patterns descend from the fabric of gills. Deposits left on paper gesture in stark formations, recalling displacement from their growth site—the underground network of the forest floor.

During an eight-to-twelve-hour exposure, a milky discharge appears, spreading in wisps or smears outside of the gills’ radius and becoming more defined closer to where the stem used to exist. Spore printing can reveal thin filaments crisp in their linemaking or their transfer can be entirely vague, producing abstract ghost-images. Here the organism conveys a composition of genetic code, and to study spore prints depends on the somewhat vulgar interference of subject to medium, those spores released and caught by materiality when they would’ve been otherwise invisible to the naked eye, or redistributed unseen in a common decomposition miracle with the earth.

Through this interaction, the images make themselves, while I act as a facilitator to bring materials together. The resulting documents provide a witness and surface for chance reaction, graphic notation of an ecosystem, and a full expression of gills. A smudge of a fingerprint can erase any contact or evidence of their existence on paper. It’s possible that tracks made in these events could have come from larvae hatching, exploring, and perishing on the terrain of the paper during the developing process. Maggots crawling tend to leave secretions in their path that look like silk strands, though the leaping choreography of these tracks suggests another kind of movement or creature altogether. This graphing becomes a kind of forensic mycology, looking at a dead body and seeing inside it. A time-lapse that is not a chain, but a matrix.

An important aspect of this project has been to record GPS coordinates where each species was found, to honor and measure the distance from the origin site and to reflect where the spores can be traced back to as another layer of survey or analogous poetry.