LUZ DEL DÍA: COPYRIGHTING THE LIGHT OF DAY

first performed on May 25, 2017

Sunken Room Gallery, Rochester, NY

performed three times in 2017

STEPHANIE MERCEDES

Buenos Aires, Argentina / New York, NY

439787290o439787290r439787290n439787290a439787290m439787290e439787290n439787290t439787290a439787290l439787290.439787290a439787290c439787290t439787290i439787290v439787290i439787290s439787290m439787290.439787290c439787290o439787290n439787290t439787290a439787290c439787290t439787290@439787290g439787290m439787290a439787290i439787290l439787290.439787290c439787290o439787290m

LUZ DEL DÍA: COPYRIGHTING THE LIGHT OF DAY

STEPHANIE MERCEDES

The performance series “Luz del Día: Copyrighting the Light of Day” reflects my inner conflict about representing and historicizing violence that is too difficult to imagine or reconcile within oneself. In the series I lead the audience through four exercises while simultaneously blending installation, oral archive, Argentinian Copyright Law, the elusive nature of the documentary image, and missing collective history.

Mixing Spanish and English I tell the the story of Argentinian Copyright Law, the role of orphaned images in history and the current status of Proposed Argentinian Copyright Bill No. 2517-D-2015. If passed, the bill would retroactively privatize the photographic archive of the Argentinian Dictatorship (1976–1983) in which the right- wing military government disappeared approximately 30,000 civilians. This series is an attempt at saving the disappearing archive.

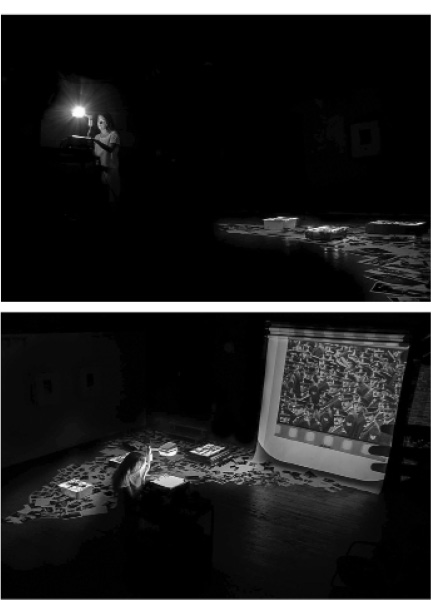

Surrounded by copies of the images that could be censored, I overlay them on the overhead projector until the images are obscured. Both the layered images and the room darken. I also start to remove images from the projector, so that light returns to the room and the images become more visible. Once I have removed all of the images, I place them all back on the projector and repeat. The audience is at first facing away from the performance and sitting with their eyes closed. They are slowly instructed to turn and face the light and open their eyes.

I’m not interested in fetishizing acts of unimaginable violence through images. I hope that by layering multiple images together and by blending performance with documentary image I question the purity of the documentary image and the singularity of memory. I see this project as a personal way of understanding my family and country’s past. While the atrocities of the past cannot be controlled, their memory should be transparent. The violent archive must remain alive.