HOW I CAN—WELL-ENOUGH (OR SHOWING MY WORK)

first performed on October 21, 2016

7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art, Toronto, Canada

performed once in 2016

ANNIE ONYI CHEUNG

Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

onyi-ajar.com

HOW I CAN—WELL-ENOUGH (OR SHOWING MY WORK)

ANNIE ONYI CHEUNG

This durational performance is in pursuit of understanding, familiarity, and connection with one who has always seemed impossibly close, and yet so far at the same time. I perform for four hours, slowly cobbling together a letter written in Chinese. I grew up in Toronto in a Mandarin- and Cantonese-speaking household. As a child, I went to Chinese school for years. I can now speak and understand the language well enough, but I have trouble reading and remembering Chinese characters. For “How I Can—Well-Enough (Or Showing My Work)” I use available digital translation tools that speak English-Chinese translations aloud for me to hear, understand, and try to remember, as I labor to write a letter that resembles my Chinese voice. I write to my father, who is alive. We have brief conversations by phone, but I struggle with our lack of closeness.

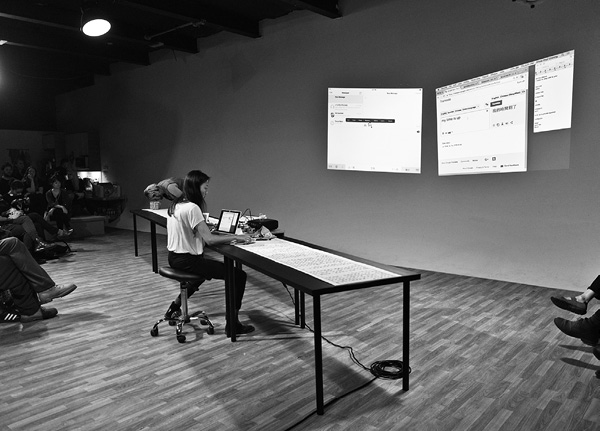

There is a long, 20-ft table at the center of the performance space. It is covered by an equally long scroll of grid paper. I begin the performance seated at the right-most end of the table. My ambition is to fill the grid with meaningful Chinese words, writing from right to left. Technology is set up on a fitted glider that moves along the length of the table with me, as I write and fill each row. The tools on the glider include a variety of stationary and my laptop and tablet, both amplified by PA speakers and connected to projectors that throw images of my screens on the wall. The tablet lets me hand-write Chinese characters that I do not remember or recognize so it can speak the character(s) aloud to me. On my laptop, I use an online translation tool that translates English phrases to Mandarin Chinese, and then reads aloud the various Chinese translations for me. I make scribbles and notations in the margins of the grid to help me remember what I’ve written and what it all means, along with phonetic notations that help me remember the Mandarin pronunciation of individual characters. The performance feels slow and paced, as I experiment with slight to wild variations of English phrases in an attempt to trigger particular familiar Chinese words and phrasing. In this way I sculpt language into familial vernacular. At the left-most end of the long table is a small, bound cardboard box that emits faint sounds. Inside: videos, glimpses of home.