THINKING IS FORM

first performed on October 9, 2013

University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC

performed once in 2013

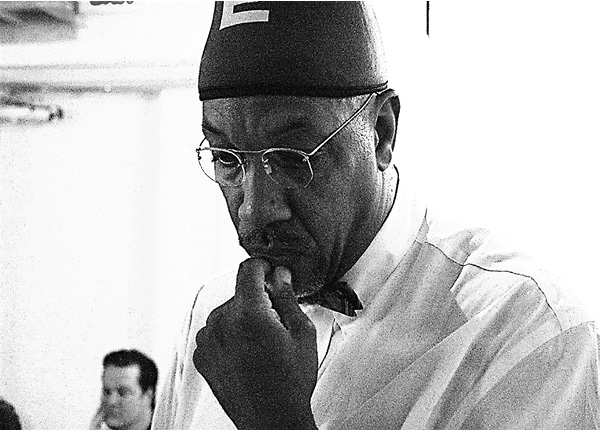

MICHAEL BRAMWELL

Cary, NC

979968466m979968466i979968466c979968466h979968466a979968466e979968466l979968466b979968466r979968466a979968466m979968466w979968466e979968466l979968466l979968466497996846699799684663979968466@979968466g979968466m979968466a979968466i979968466l979968466.979968466c979968466o979968466m

creative-capital.org/onourradar?id=23868

THINKING IS FORM

MICHAEL BRAMWELL

There is no more light in a genius than in any other honest man, but he has a particular kind of lens to concentrate this light into a burning point.

— Ludwig Wittgenstein, Culture and Value.

“Thinking is Form” is a performative work that investigates the invisible structure that houses academia by making it visible once again. Academia often palms itself off as an independent and creative institution supporting freedom and inclusiveness, while in effect it often functions as an ideological construct that perpetuates myths of western cultural supremacy. This work uses performance art as a methodology for institutional critique. It appropriates its title from a 1993 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York that featured drawings by post-war German artist Joseph Beuys. One of his fundamental messages delivered in lectures and artworks was that “everyone is an artist,” that everyone has a capacity to apply creative thinking in their own area of specialization—which are the fine arts in this instance.

This performance consists of seven folding utility tables, twenty-nine chairs, forty contemporary art books and a suite of framed paintings on paper (Discourse on the Maafa, 2013) hanging on a wall in the critique room at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. I dressed in a white shirt, red plaid bowtie and wore a blue dunce cap while cool jazz played in the background. For this work, I collaborated with Professor Pedro Lasch of Duke University and Dr. Allmendinger, Director of Academic Programs at the Ackland Art Museum, to provide simultaneous art lectures to graduate students, professors and invited guests from the neighborhood as they sat at tables perusing art books. Throughout the performance, I wrote repetitive lines on a chalkboard (“I will learn about contemporary art”), drew street games on the floor with chalk (an ideological tool) and stood facing the wall in various corners around the room. Each individual had to think for themselves and decide what was important to focus on, despite the restrictive formal structure and overstimulation they had to sit through as a requirement of the graduate critique process. What became evident was that freedom of thought was, in reality, thought of as conformity rather than as independence. The scarcity of artists of color in the program, among the faculty, and of multicultural artworks represented in the art books is evidence of the constraints of ideological thinking. The combination of music, simultaneous lectures, written texts, art works and performative elements all created a state of overstimulation that validates the truth of Albert Camus’ observation that “the only thought to liberate the mind is the one that leaves it alone.”