POULTRY PARADISE AND ITS DISCONTENTS: NIGHTSHIFTS

first performed on September 6, 2013

Panoply Performance Laboratory, Brooklyn, NY

performed once in 2013

KIKUKO TANAKA

Eric Heist, Phillip Gulley

Brooklyn, NY

822028053p822028053i822028053s822028053s822028053q822028053u822028053e822028053e822028053n822028053@822028053k822028053i822028053k822028053o822028053w822028053o822028053r822028053l822028053d822028053.822028053n822028053e822028053t

kikoworld.net

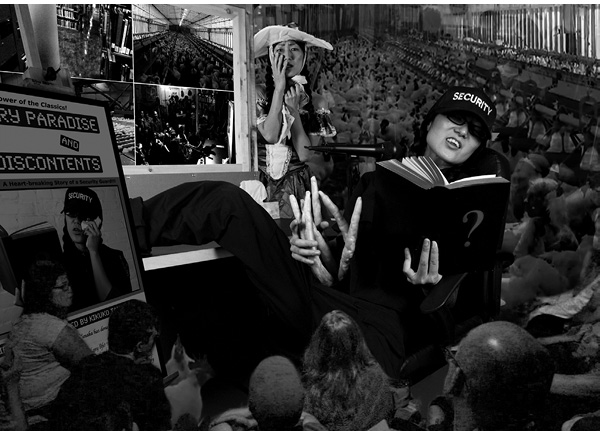

POULTRY PARADISE AND ITS DISCONTENTS: NIGHTSHIFTS

KIKUKO TANAKA

“They were themselves intellectuals, as is anyone and everyone. They were visitors and spectators, like the researcher who a century and a half later read their letters in a library, like the visitors of Marxist theory or the distributors of leaflets at factory gates.” —Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator

In my first decade in the U.S., I worked at a nightclub. When I was bored, I entertained myself by imagining other night workers awake throughout the night. There were some surveillance cameras there, and I imagined a person on the other end of the cameras who would probably not be looking at us at all.

Partly based on a displaced and imaginary autobiography, “Poultry Paradise and its Discontents” is a nightmarish farce or melodrama framed as a “tragic theater play” which invites spectators to contemplate the blurred distinction between individuality and collectivity, the function of literary/artistic canons, the relationship between artist/intellectuals and plebeians and the infectiousness of enlightenment and democracy.

The performance begins as a reception where I pose as an 18th century-society-lady, socializing with the audience and encouraging them to visit my art & philosophy salon. I praise the play in an overly exaggerated manner, claiming that “this play has changed my whole life. Overwhelmed by a sense of pity, I emerged from a bale of tears as a completely new person!”

I disappear into the backroom and reappear as a security guard. I sit in front of the large split security monitor that displays the quiet scenes of a library, a poultry factory and a live-surveillance of the spectators themselves. I completely neglect my job and begin reciting from a thick mysterious black book.

The texts are sampled to emphasize the most ridiculous or problematic sections of Maldoror by Comte de Lautreamont and Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, which may resemble the experience of a “non-Western immigrant security guard.” The Mystery Book includes the story of a self-marginalizing lonely hermaphrodite longing for membership in human society, attempting to learn their human language and sentiment. The story, like Frankenstein, covertly expresses the supremacy of Christianity and Western democratic virtue over the Orientals.

As I read, I begin touching my loins and eventually pull out a many-headed phallus from my pants. I recite, masturbate and sob through the rest of the performance. The text culminates in the concept of the “rights of who does not have rights” that Olympe de Gouges, a revolutionary playwright, fashioned at the wake of the modern world. The performance ends as I read the scene of the decapitation of Olympe de Gouges at the hands of revolutionary terror.