LOVE.ABZ

first performed on

October 14, 2011

Prelude 11, New York, NY

performed four times in 2011

OTSO HUOPANIEMI

Emily Catherine Copplestone, Emily Gleeson, Federico Rodriguez, Eeva Semerdjiev (performers) and Hannah Hessel (dramaturg)

Helsinki, Finland

742050407o742050407t742050407s742050407o742050407.742050407h742050407u742050407o742050407p742050407a742050407n742050407i742050407e742050407m742050407i742050407@742050407y742050407a742050407h742050407o742050407o742050407.742050407c742050407o742050407m

web.gc.cuny.edu/mestc/events/f11/prelude/artists/huopaniemi.html

LOVE.ABZ

OTSO HUOPANIEMI

“love.abz” is a writing as opposed to a reading-an act of digitally mediated, collaborative live writing. It deals with questions of translation and drama.

What if dramatic writing were to happen during the performance instead of before it? What is at stake for me as a playwright is an act of withdrawing from authorship and making way for a form of collective writing improvisation that involves human-computer interaction. At one point, I thought of the computer as one of the writers. Now I see it as a device that enables a simulation. A simulation of the impossibility of writing…

The tools we use are machine translation and speech recognition. The audience sees the processes in progress from an upstage projection. Writing in Finnish, I use Google Translate to address the audience directly-to the extent that the program allows it. The actors use speech recognition software to write dramatic scenes. We time the improvisations and have a synthesized voice-the invisible fourth actor, “Alex”-read the scenes out loud. I’m standing behind a podium. Once I’m done introducing the piece and the performers, the actors and I switch places. For me, this is the most significant moment of the piece. This is when I concretely make space for words other than my own-insofar as I have ever owned words to begin with.

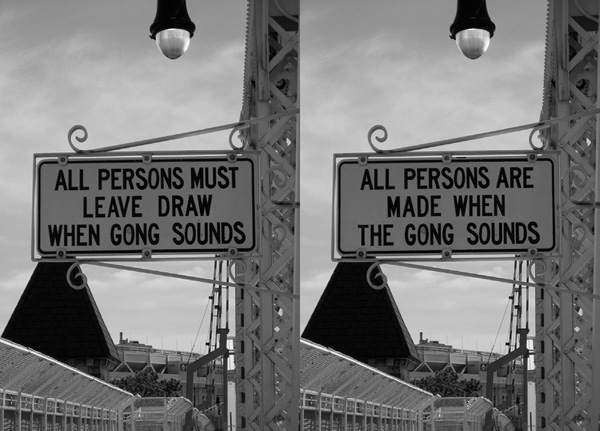

When I ask the actors if they’re ready, they respond, “Yes! Kyllä!” Then the actual writing begins. The process is time-consuming and agonizing at times, misrecognitions abound. The suspense of recognition… The crucial question is what to do when the computer makes a mistake. To yield to the misrecognitions and build on them, let them lead the improvisation, or to resist them? This is the drama. This determines the power relationship between the computer and the human writer. It determines the stance the piece takes on digital mediation in general. Yielding to the mistakes and allowing the errors to guide the improvisation seems to be more fun. Yet what are we-the performers along with the audience-laughing at when we laugh at this mistake-ridden process? The fallibility of the computer? Our persistent belief in technology? Or writing itself. The impossibility of conveying meanings via language. Writing is a process that never quite reaches its target. The frustration resulting from this unattainableness is externalized in this simulation, made visible by the dysfunction of the human-machine interface.