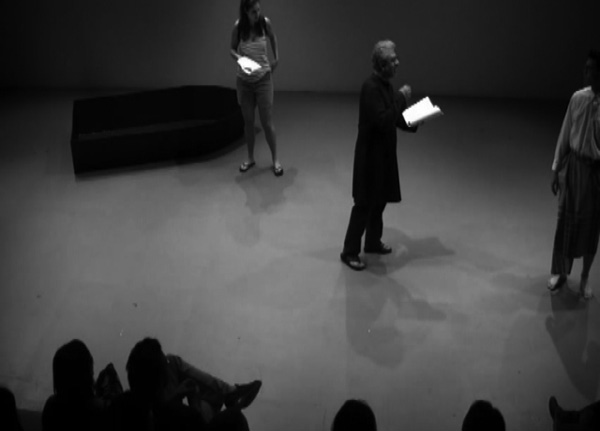

THE ISLAND

first performed on

April 11, 2011

Dixon Place, New York, NY

performed once in 2011

FLY BY NIGHT THEATER

Matt Reeck

154549287m154549287a154549287t154549287t154549287.154549287r154549287e154549287e154549287c154549287k154549287@154549287g154549287m154549287a154549287i154549287l154549287.154549287c154549287o154549287m

THE ISLAND

FLY BY NIGHT THEATER

“The Island” addresses the problem of identity politics, or the stereotypes we assume from the identity-related information that appearance provides. This happens within the play and between the audience and the actors. Of the play’s three characters, two have unstable identities. The Woman finds the Boatman standing next to a boat, but he isn’t really a boatman (the boat is his brother’s). In addition, the Guide is really a religion student, willing to serve as a guide for uncertain, perhaps nefarious, reasons. The play tempts the audience to misread identity-related aspects of its staging. The play never names its setting, and the characters themselves aren’t named. It takes place in a zero-space, or minimalist, existential one, in which clues (cues) for nation, race and religion are few and, when present, send mixed messages. Casting choices help confuse the sense of place and identity. The Boatman and the Guide share a language that the Woman doesn’t, but they are hostile to each other, marking them as relatively foreign as well. Then, the persons playing these two roles must clearly not be from the same “native” country: they must be different races. This frustrates the audience’s ability to fill in absent identity-related information by extrapolating from “real-world” details read off the actors’ bodies. Instead of coming to a firm conclusion, the play hopes to invalidate whatever stopgap answers the audience arrived at during its course.

The situation of this play is roughly postcolonial, and as such echoes Edouard Glissant’s poetics of relation. Glissant argues that cultures are largely opaque to each other, and when persons of different cultures inhabit a shared space they should approach each other slowly and with the constant expectation of strangeness. The world may be uniformly visible, but its visibility can be the immediate source of error when we facilely over-read, or over-interpret, its signs. “The Island” riffs on this sort of projection. The Woman has uncompromising but naïve expectations about finding a particular wall on a particular island that her guidebook asserts exists but about which the natives are ambivalent. Yet they are eager to please, and they don’t seem to have anything better to do. They go along with the Woman, trying their best to satisfy her, reshaping an ambiguous reality to meet her demands for factuality and clarity.